Julius Civilis and his complices swearing the oath (Rembrandt)

This text is based upon 'The Histories' by the Roman historian Tacitus, supplemented by modern sources

|

|

|

Julius Civilis and his

complices

swearing the oath (Rembrandt)

A sacred forest in the Rhine delta (currently the Netherlands), the summer of AD 69: the leaders of the Batavians come together to attend a banquet. One of them, Julius Civilis, takes the floor. He speaks about Roman oppression and points out that the civil war in Rome has seriously weakened the Roman garrisons in Germania. So, the time has come to raise a revolt. The leaders swear an oath of mutual allegiance and they send messengers to the Cananefates in the coastal area, inviting them to join the rebellion. War is on!

On the site of what is now the city of Nijmegen in the Netherlands, there lay a larger military camp (castra) called Oppidum Batavorum. Here, the Romans later founded the city of Noviomagus. Most important city in the province was Colonia Agrippinensium (present-day Cologne). About halfway between the two lay the military stronghold Castra Vetera (present-day Xanten, Germany), which was to play an important role in the war to come.

West

of Oppidum Batavorum, between the Rhine-Waal and Maas rivers, lay the

homeland

of the Batavians, a Germanic tribe that cohabited with the Roman rulers

under the terms of a treaty: unlike most submitted peoples, they were

exempted

from taxation, but were reserved for employment in battle. Initially,

this

meant that they served occasionally as tumultuarii or

irregulars

under command of their own leaders. After AD 40, the Romans began to

enlist

Batavians in regular auxilliary formations, meaning that military

service

turned into a full-time occupation

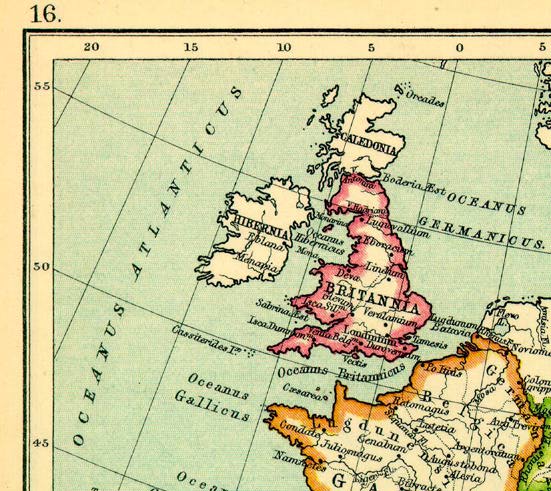

Geography of the

war theatre (The Netherlands, Belgium and the German Rhineland) with

modern

place-names and the names of the Germanic and Gallic tribes (Italic)

In

the coastal area lived the Cananefates, another Germanic tribe, which

had

close ties with the Batavians. In the North, across the Rhine, lived

the

Frisians, more or less free from Roman rule. The Batavians and

Cananefates

served in the auxiliary forces attached to the Roman legions. Batavians

served as imperial bodyguards in Rome as well.

For fourteen

years,

Nero had been -even by Roman standards- an incompetent and cruel

emperor.

He was forced to commit suicide in AD 68. His successor, Galba was murdered,

after having been in power for only seven months, in what was to become

the 'year of the four emperors' AD 69. His successor Otho was an

emperor

for only three months and committed suicide in the same year. His

situation

had become hopeless after military defeat inflicted upon him by troops

loyal to Vitellius, a general of the army in Germania. Vitellius's

position

as the next emperor was immediately challenged by Vespasian, an army

commander

in the Middle East, who eventually was to defeat Vitellius and was to

emerge

as the fourth emperor in AD 69. At the time when Vitellius was facing

the

threat of Vespasian, the revolt in Germania Inferior broke out.

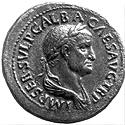

Galba

GalbaOtho

Vitellius

Vitellius

Vespasian

The obligations of the treaty with the Romans posed a heavy burden on the Batavian community. Out of a population of 40 000 souls, about 5 000 men in their finest years had been taken away from their homes and families to far away places for 25 years of military service. Due to the civil wars, the Romans were in desperate need of more troops. Pressure on the Batavians was increased until it became unbearable, even more so due to the brutal behaviour of the recruiting sergeants, who tried to extract bribes and abused the young men. The Batavians must have become desperate and motivated to throw off the yoke of oppression.

The civil war offered the Batavian leadership a golden opportunity to act. Never before had the strategic situation been so favourable. Not only was the Roman military power in Germania seriously weakened, as so many troops had been summoned to Rome to defend Vitellius, but the situation enabled Civilis to pretend to act in support of Vespasian and not as an enemy of Rome. In fact, Civilis had been persuaded by high-ranking Roman officers, supporters of Vespasian, to prevent Vitellius's reinforcements to leave Germania, by simulating a rebellion. This suited him perfectly: he could start the revolt with Vespasian's consent and without, for the time being, having to give away his hidden agenda.

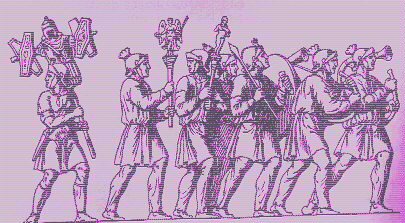

Roman

soldiers

The Batavians and their allies could count on their tribal warriors. Though these would prove very useful in guerrilla type operations, their skills in large scale warfare were limited. To change the military balance, Civilis needed more disciplined formations trained in conventional warfare. Such troops were the Batavian auxiliaries serving in Germania. Some of these, among which were the Ala Batavorum, a cavalry formation, changed sides as soon as they were thrown into battle against the rebels. Other formations, known as the eight Batavian cohorts, an elite fighting force of formidable reputation, were already on their way to Italy as a reinforcement to Vitellius's army, when hostilities began. Civilis managed to contact these troops just in time. They did not hesitate and returned to join the rebels. With these auxiliaries, involving about 5 000 of the best soldiers, Civilis managed to change the military balance.

Statue

of Arminius

Given the military situation, the rebels had a fair chance to overrun the Roman army in Germania. But what if the civil war would come to an end and the Roman Empire would again be in the position to retaliate? Civilis found inspiration in past German uprisings. In AD 9, Arminius annihilated three Roman legions in the Teutoburger Forest, East of the Rhine. Since then, the Romans had practically given up the dream of expanding their empire beyond the Rhine. He mentioned this historical event in a speech to the troops in the early days of the revolt. The uprising of the Frisians in AD 28, brought about by greedy tax gatherers, though of much less importance, had had similar consequences.

The remaining frontier forts in the region were set on fire and abandoned, because they could not be defended. In august AD 69, Civilis managed to force the retreating Roman troops to a battle in the upper river delta (Betuwe). German auxiliaries changed sides and so did the Batavian rowers of the Rhine fleet, which subsequently fell into the hands of the rebels.

After this

painful

defeat, Hordonius Flaccus, commander in chief of the Rhine army,

ordered

a counterattack. The remnants of Legio V and XV were sent from

Vetera

to the Betuwe to fight the rebels. These troops were intimidated by

their

opponents showing the field signs captured in the prior battle. The

rebel

warriors, defending their homeland, got psychological support from

their

women and children positioned in the rear as a spur to victory or a

reproach

to the routed. As soon as the Ala Batavorum (Batavian Cavalry) changed

sides, other auxiliaries panicked and the legionaries retreated to

Vetera.

Detail

of the famous 'Peutinger map' (Tabula Peuteringiana), a medieval copy

of

a Roman road map. In the upper left quadrant it shows Lugdunum

(Katwijk)

and Preatorium Agrippinae (Valkenburg). At these locations lay the

Roman

castella that were captured and sacked in the first stage of the

uprising.

(click on the picture to see a sharper black and white copy of the map)

Roman

settlement at Xanten, close to the destructed Castra Vetera

(reconstruction)

Roman

settlement at Xanten, close to the destructed Castra Vetera

(reconstruction)

The Romans still had parts of six legions in Germania, adding up to a total of more than 15 000 men. Two of these incomplete legions were located in Germania Superior and four in Germania Inferior: one in Bonna (present-day Bonn), one in Novaesium (present-day Neuss), and two in Castra Vetera, the most Northern stronghold in Germania still in Roman hands.

Castra Vetera was a rectangular camp of about 900x600 metres, which was quite large given the number of defenders. It's walls consisted of a wooden palisade on a ditch (unlike the stone walls on the picture). It had not been designed as a fortress which could offer protection against something so unlikely as an attack by a German army. So, Vetera seemed an easy prey to Civilis and the reward would be large: once the Romans had been kicked out of Vetera, their position in Germania would become hopeless.

Civilis, whose army had been reinforced by now with German tribes from the other side of the Rhine, wanted to take Vetera by brute force. But all attempts failed. Even though the Germans employed engines-of-war, the defenders proved more skilful in this type of warfare. So, the Germans decided to starve them out.

The Roman supreme commander Flaccus decided to send a release army under Vocula. This army halted in Gelduba (present-day Krefeld), about 40 kilometres from Vetera. The Romans however, were reluctant to act.

New attempts to take Vetera also failed and in November, Civilis decided to send an army to Gelduba to attack the Romans there. Though initially the Germans were successful, the battle ended in defeat because the Germans panicked when, coincidentally, some cohorts of auxiliaries entered the stage. The Germans had to retreat. Especially the Batavian cohorts had to leave many casualties behind. This was the moment for Vocula to complete his mission. He sent his troops to Vetera and threatened to deal another blow to the Germans. In a winning mood, the troops from Vetera broke out and this was too much for the Germans. Vetera was set free.

To make things worse, mutiny broke out among the Romans. The soldiers, who hadn't been payed for quite some time, were fed up with their commanders. As the majority of the troops stood firmly behind Vitellius, they eventually murdered Flaccus, who was an alleged partisan of Vespasian. Vocula, who was also in danger, managed to escape.

In the meantime Civilis resumed the siege of Vetera. The garrison was slowly strangled by starvation. Early in AD 70 Vocula sent an army to prevent the fall of the fortress. This army and its commanders consisted mainly of Gauls. Julius Classicus, a high ranking officer of Gallic origin, conspired with Civilis to form a Gallo-German empire as soon as the Romans were definitely driven out. Under these circumstances the position of Vetera became hopeless and the garrison surrendered. This victory had been foretold by the prophetess Veleda, who lived in a tower in the land of the Bructeri, near the river Lippe. Civilis sent the Roman commander Munius Lupercus to her as a gift, but he was killed before he reached her. The vanquished troops were granted a safe retreat. However the victorious Germans broke their promise and the legionaries, while on the retreat, were ambushed and massacred by the Germans.

At this point the rebels were at the peak of their power. The remaining Roman forces, mainly auxiliaries, changed sides. So, Roman military presence in the Northern provinces had ceased to exist. But this situation was not going to last very long. In Rome, Verspasian had defeated Vitellius. Civil war was over and time had come to restore order in the empire, especially in Germania.

Roman

amphitheatre in Trier

Roman

amphitheatre in Trier

To restore Roman rule in the rebellious provinces, Vespasian launched a campaign, employing eight legions under Petilius Cerialis. Five legions came from Italy across the Saint Bernard passes in the Alps, two came from Spain and one from Britannia. In the meantime, the victorious Germans and Gauls failed to coordinate their actions. The Gallo-German empire did never come near to reality. The leaders lacked the ability to build up and rule such a large entity. Moreover, they were too preoccupied with their own affairs, to even organise their defence.

The Romans penetrated Germania Superior, where it came to an unexpected clash between the opposing forces. Cerialis entered the city of Treveris (present-day Trier) at the river Mosel. Here he arranged a meeting with the regional leaders. On this occasion he delivered a famous speech to them, pointing out the blessings of Roman rule and giving them the choice: submission or death.

In Treveris, a Gallo-German army attacked the Romans by surprise. The fierce battle that developed, almost resulted in a Roman defeat. However, Cerialis miraculously managed to drive the Germans off. They would certainly not get a second chance and from that moment on, it was only a matter of time before the Romans put an end to the revolt.

The text of

the

Histories breaks off here. So, the final outcome is uncertain.

Historians

assume that the Romans renewed the treaty with the Batavians on the old

terms. This is in line with a passage in book VII of 'The Jewish War'

by

the contemporary historian Flavius Josephus. There is plenty of

evidence

regarding the existence of Batavian formations in the Roman armed

forces

until far into the third century. The Romans, however, wisely deployed

these formations far away from their homeland: in Britannia and in such

remote places as Pannonia (Hungary) and Dacia (Romania). In the

following

centuries, the Batavians eventually vanished: they probably merged with

the Germanic peoples (mainly Franks and Saxons) that settled in the Low

Countries during the Migration of Nations.

|

|

|